The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

3 posters

Page 1 of 1

The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

Donald Hall

Today 12:19pm

The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

The following was originally published in the Dec. 1986 issue of Sport magazine. It is reprinted here with the author's permission.

Last year the City of Boston erected a statue of Red Auerbach in the Faneuil Hall Marketplace near the effigy of James Michael Curley, another shrewd benefactor of Boston who once was reelected mayor while serving a term in jail. In his latest hurrah, the bronze patriarch of the Boston Celtics sits on a bench upright and alert; fans and tourists sit beside him and get their pictures taken. He carries a clenched program in his left hand where the ring finger wears the jewel of an NBA championship. In his right hand he clasps an enormous bronze cigar, fondled so much by admirers that it shines like St. Peter's toe.

The statue's original keeps a large and cluttered den on Causeway Street in the Celtics' offices, which are connected by a bridge of sighs to the great leaky ark of Boston Garden. As I enter the office, the the first thing that greets me is a life-sized cutout of Red Auerbach smiling and gesturing—a two-dimensional statue which I start to address. While I sit facing the man, his cardboard image hovers over my right ear; when one Red Auerbach answers the telephone, I swivel my head to find another Red Auerbach looking down at me.

Auerbach's office occupies the building's corner with windows on two sides, so that you can look down at the surviving elevated tracks of Causeway Street. The glorious junk of a lifetime overflows this room. Several hundred photographs on the wall mostly picture tall young men wearing shorts; the family pictures of the multitudinous sons. I count at least 20 caricatures of the father figure himself. On the desk, on a table and on shelves extending from a wall are dozens of letter-openers from Auerbach's extensive and global collection: blades that look like steel, ivory, pewter, bronze; handles of ivory, gold, cloisonne, enamel. The whole collection approaches 500, but much of it stays in Washington, where Auerbach has retained residence while commuting to Boston for 36 years. On the wall hangs a jacket from the Washington Caps, Auerbach's first stop as a professional coach, in 1946. There are framed citations, trophies galore, mementos that look like toys for grown-ups—a small cannon, a boomerang, basketball dolls—a painting that features Jo Jo White, plants, books and wood sculptures that look African and Oriental.

He hangs up. We talk. In July of 1986 Arnold (Red) Auerbach has come north to Boston for the first time since his latest sports injury. Playing tennis earlier in the month, this sexagenarian leapt for a ball like Larry Bird (whom he beat on the courts several years ago; "How can you let yourself be beaten by a 65-year-old man?" taunted Auerbach) and laid himself up. "I dove for the ball. Boris Becker! A poor man's Boris Becker! I just dove flat out for it, got the ball back and tried to roll over… bang! I hit the deck and broke two ribs." It is noted that he got the ball back; it is noted that he lets us know he got the ball back. This is the same ancient fellow who, three years ago in exhibition season, lost his temper and tried to assault Moses Malone. When I remind him he laughs. "Billy Cunningham called me up the next day. 'Goddamn!' he says. 'You never change!' " As he laughs the lines that ray from his eyes deepen, and for a moment he looks like a man in his 70th year. He sits slightly stooped, his once red hair a sparse grey. His physical self seems shrunken, or at least smaller than the whole presence of the man. But the energy that he exudes—even lounging back in his chair speaking mildly—removes the wrinkles one by one until his age is invisible.

Red Auerbach intends to work out three times a week—"racquetball, tennis, something to get a little sweat up"—but he no longer challenges his players at HORSE. "As you get older," he acknowledges with a sigh, "the ball gets heavier." His former all-star Bob Cousy, 11 years younger than Auerbach, meditates now on "banking the fires of competition," as he tells me; if you are unable to cool down the flames, says Cousy, the author of The Killer Instinct, they burn the lining of your stomach.

When I mention Cousy's endeavor, Auerbach nods his head. Leaning back in his chair, puffing at his logo, surrounded by trophies of the life lived, he speaks softly: "It's just age," he says. "You've got to learn to adjust to the limitations. It's difficult…" I realize that, unlike his old point guard, Auerbach struggles with match and kerosene, not with fire hose; Cousy is not president of the Boston Celtics. "You try to keep up the fire," says Auerbach, "but you find that you need, oh, a little more rest… a little more away time." He blows out a great, enveloping, blue cloud; it smells good. "If you don't have that driving interest, it's transmitted to the coaches and players; they feel it."

He has been speaking almost dreamily, in a soft voice rather high in the register, milder and more reflective than I had expected. In his autobiography he called himself an introvert, which startled me until I realized that everybody, even the wildest public man, knows in his secret heart that he is an introvert. When I questioned him about the word, he explained, "It's a guy that likes his own privacy."

Suddenly he blasts me out of my chair with a booming horn of a voice, as he looks past me to the corridor outside. His voice drops eight octaves and rises 400 decibels; his accent becomes street-Brooklyn, like Archie in the old "Duffy's Tavern": "Hey! M.L.! Don't go away!"

Leaning gracefully against a doorjamb is the tall and elegant form of M. L. Carr, who played in the Celtics' backcourt from 1979 to 1985. As I catch sight of him he pirouettes lightly, stylish as Baryshnikov—and dressed to the nines in polished shoes, crisply creased grey flannels, green blazer, white shirt and striped tie. He tilts his head back to regard Auerbach who bellows again: "M.L. Don't go away!"

M.L. adopts a studied look of puzzlement and speaks in a teasing, high-pitched, pondering voice: "Now that's interesting, you tell me that… a year ago, you told me to go away!"

Red Auerbach laughs. "Okay," he says. "Go away but don't stay away."

We all know whose shrewdness assembled this team. For 20 years Frenchified sportswriters, talking about the Boston Celtics, have gone to Larousse to spell the ineffable; they find mystique, easily the most overworked gallicism since Chevrolet coupe. Dissidents have been quick to repair the orthography: R-u-s-s-e-l-l in one era, and B-i-r-d in another. But the true orthography—in one era and out the other—is A-u-e-r-b-a-c-h, and there has never been another such institution in American sports. In 16 years as the coach he won nine championships; in 36 years of running the show, he has collected 16.

Houdini—or call him Diaghilev or Peter Sellars or Thomas Alva Edison—began life in Brooklyn in 1917, son of an immigrant from Minsk who worked his way up to owning a dry cleaning establishment. (Auerbach still presses his own trousers on occasion at a friend's shop; it takes him back.) His father Hymie's character, Auerbach says, differed from his own: "Everybody liked him." He admires his father and like many men who admire their fathers, he admires fatherhood. To his team he has been protective, fair, difficult, tender, demanding and above all, paternal.

The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

Although he admires his father's easy popularity, he made good use of his own abrasiveness. "At first I didn't like Red Auerbach," says a rival coach, "but in time I grew to hate him." If you spend energy hating Red Auerbach, maybe you do not play so well against him.

In street and schoolyard, young Auerbach became an athlete, as sport provided exit from Brooklyn to college by way of scholarship. His potential as a pro was not an issue in 1940, when he could pick up $20 maybe by driving to Wilkes-Barre to play semipro. He had majored in physical education in order to become a teacher and a coach. After college—team captain his senior year, high scorer—he picked up his M.A. at George Washington University while coaching at St. Alban's Prep in Washington. He worked for the city on playgrounds, refereed and then taught while coaching at a Washington high school. An early academic triumph was the publication of an article in the Journal of Health and Physical Education in March, 1943, on the construction and utility of indoor obstacle courses. (High school students trained for combat in 1943.) In 1986 in his office on Causeway Street, Red Auerbach reaches into a bookshelf and hands me the Journal, opened to his paper. "I had the centerfold, see? 'A.J. Auerbach, Roosevelt High School, Washington.' "1

Even when you are 69 and there is a statue of you in town you take pride in the byline that glorified your 26th year.

After three years in the wartime Navy, Auerbach began his professional career in 1946, coaching the Washington Caps of the newly founded Basketball Association of America. In 1950 he came to the Boston Celtics. He was hired by Walter Brown, who owned the team and was losing his shirt. In recent years a ticket has turned hard to come by; it was not always so. When the Celtics with Bill Russell won 11 championships in 13 years, they sold out only for playoffs. Basketball was for New York and Indiana; in the north country, hockey was the sport.

The New England exception was Holy Cross, and chauvinist sportswriters ignorant of basketball made a shrine of Holy Cross—1947 NCAA champs, a 27-4 record in 1949-50. That spring when Auerbach, at his first news conference as Celtics coach, was asked if he would draft the great Holy Cross senior Bob Cousy, he referred to the demi-God as a "local yokel." Enemies he made in that moment hectored him for decades. Later, in order to stop an idiot chorus claiming that Holy Cross could beat the Celtics, Auerbach scheduled a scrimmage; predictably, pros kicked college ass.

Auerbach's notions about roundball were set long ago. He praises his coach from George Washington University, Bill Reinhart, and he repeats the theme that the game has not changed. Bodies get taller and quicker but the game is the same. "I was always a fundamentalist. Like my book." He refers to Basketball for the Player, the Fan and the Coach. "It's in seven languages. It was written in 1952. Most of it is applicable to today's game."

There have been innovations and he has not always favored them. Twenty years ago he was vehemently against the suggestion that the NBA install a three-point shot. "I was wrong," he says quickly. Over 69 years you have the opportunity to be wrong about many things, and the president of the Boston Celtics is quick to proclaim his error.

Of course many modern wrinkles are Auerbach's own, tried out not in practice or even at rookie camp but on schoolyards in the Washington summer. When Auerbach relaxes from professional basketball there is nothing he likes so much as to watch basketball. "I go to watch high school. Even today, it's nothing for me to go watch a summer league. I go out to Maryland or Georgetown or George Washington, and I watch teams practice.

"Some of the best plays I ever devised were on the playgrounds. We'd get there early, guys like Elgin Baylor, Dave Bing, guys around Washington, even as professionals, working out on a Sunday morning in the playground during the summer. Sometimes I'd get there a little early, and I'd say: 'Look, I've got an idea.' If we could do it on the playground, we could do it in the NBA. That's where I invented all those out-of-bounds plays, when people line up across the court."

He stubs his cigar out in an abundant ashtray. From time to time he glances into the corridor. I ask: "Do they keep coming back, like M.L.?" He nods: he is happy. The sons return; they grow potbellies and grey hair, but they are sons and they return. "I talked to Ramsey just two days ago. I know where every one of them is. Gene Conley down the street, Finkel, Kuberski, Satch, Havlicek. When they're not around, I talk to them; I talk to Macauley; I even see Bones McKinney now and then." Bones McKinney was a 1946 acquisition for Auerbach's Washington Caps; he played for the Celtics late in his career. Although Bill Russell lives in Seattle, "I see him all the time because he works for TBS. I see his daughter. She's at Harvard Law School. I see her all the time."

In a moment he walks around the desk to the great humidor of cigars. He offers me one which I refuse; then I change my mind. I pick one out and cherish it into an inside jacket pocket.

Auerbach's affection for Bill Russell bobs up continually as he speaks, and when he talks about the particulars of basketball his examples are Bill Russell first. "Who is the best athlete you ever coached?" He will list Cousy, Sharman, Gene Conley (who played major league baseball and basketball at the same time) but first he will say, "Russell was a great athlete!" Even more than his athletic ability, it is Russell's integrity and brainpower that Auerbach returns to again and again. Integrity, and frequently the want of it, is an Auerbach theme. There is a tolerable difference for Auerbach between doing everything to win a game—everything legal—and going back on your word. He is old fashioned and upright about handshakes and agreements. "Integrity" and "brightness"—both attributes of Bill Russell—salt his speech. "He is very bright, Russell, very bright."

The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

There are other favorites, even outside basketball. His daughter Randy works for Mel Brooks; Brooks has become an Auerbach crony: "I went over there with Larry Bird one time, and he entertained us for an hour and a half!" He laughs and shakes his head; he cannot provide examples. Brooks is a good man, who cares for the people around him, he tells me. Then he adds, "He's not only funny, he's bright."

I talked with Bob Cousy a week before seeing his old mentor, and Cousy handed me a ticking package: He suggested that I ask Arnold (as Cousy likes to call him) if the Celtics had recently instituted a racial quota system. Predictably, Arnold glowers: "He's kidding," he says quickly.

There are many ways to hate the Boston Celtics. Recently a prestigious form of Celtic hatred has become disapproval of their pale lineup. Residents of Princeton, New Jersey—a city noticeably monochrome—shake heads noticing that gray-boys form two-thirds of the Celtics' team; Knicks fans who live behind doormen on Sutton Place deplore the Celtics for starting three whites out of five; in Los Angeles film producers driving DeLoreans regret the irrefutable fact that the Celtics can play six whites not including Larry Bird and Kevin McHale. Never has so much civil rights fervor been expended in the service of athletic partisanship by so many rich white folks.

Any ground for suspicion lies not in Celtics history but in the city where the Celtics practice their craft. Boston is infamous for racial intolerance and so are its Red Sox. But Auerbach's record is clear. Which team in the NBA was the first to draft a black player? Which was the first to start five black players? Which was the first to hire a black coach?

Auerbach refuses to take credit. If you take credit for playing blacks you must take blame for not playing them. "It's all crap! If a guy can do a job we don't care about his color. It just happens!"

I expected Red Auerbach to be shrewd, smart and competitive; he is all these things—and he is softer than I expected, less harsh and more of an aesthete, even as an observer of basketball. The fast break is his favorite play for winning, and winning is his favorite occupation—but for the beauty of it, his favorite play is the pick-and-roll; "It has to be timed just so; the guy with the ball has to make a decision whether to go, to shoot or to pass." As he speaks his hands gesture and he smiles with something like tenderness; he is like a gourmet describing the best omelette he ever ate, or a theater-lover the best Hedda Gabler. Red Auerbach loves precision of execution—in basketball, in tennis, in baseball and in letter-openers.

For 20 years and more, Auerbach spent part of each summer in Europe, Africa and Asia, generally accompanied by a large assistant, to give clinics and spread the word about the American game, NBA version. He loved these trips, sponsored by the United States Information Agency of the State Department. He took Don Nelson with him, Bill Russell of course, John Havlicek, Tom Heinsohn, Bob Cousy—to Japan, to Taiwan, to Burma, to Bangkok and all over Africa. Wherever he went, he held his clinics in the morning, so that in the afternoon he could shop. "I bought silver, ivory, cloisonne... I know a lot about that stuff." While teacher Auerbach was holding clinics in basketball for citizens of Bangkok in the morning, in the afternoon he was teaching silver, ivory and cloisonne to his tall dependents.

I ask him: "Is your Washington house full of this stuff?"

He shakes his head smiling; it is another happiness, like his continuing friendship with old players. "Unbelievable!" he says.

Red Auerbach's two daughters grew up in Washington among the unbelievable possessions, but largely in the absence of their father. I have never talked to a grossly successful man, late in his life, who did not regret the childhood of his children. Auerbach's team-family took precedence over the family of flesh. These days he sees more of his real family—and he wants them to have things now, not after he is dead—but continually he argues with himself about the years of separation. "If anybody ever tries to tell you that they are not affected at home by what happens on the court, they're lousy coaches. Bad as it was, being away from my family, it was a blessing in disguise. Most coaches with their wives are relatively unhappy."

He still flies to Boston for many home games and listens in Washington on a radio to the rest, hearing the redoubtable Johnny Most (greatest Homer since the blind poet). He also leaves home to lecture, maybe three or four times a month. Sometimes he talks for bread and butter, often he talks for charities; he lectures at Harvard five times a year, a class in sports law.

Every summer he comes to Boston for rookie camp, and at the same time he runs his own one-week basketball camp—with college players as counselors. Len Bias was a counselor at Auerbach's camp for three years, which was how Auerbach came to know and cherish him. The death of Len Bias is not for talking about. It is the only true darkness I feel in this man. When I mention Len Bias I feel like a ghoul. Auerbach swivels his chair aside; he looks away for the first time in the interview; his mouth does not want to open. For Red Auerbach, this is the worst thing that has happened in all the years of basketball.

As I prepare to leave, I ask Red Auerbach a final question which I keep to the end because I figure that I won't get anywhere with it. In a sense I don't, because it is the only question that makes him impatient. I ask: "Do you think about dying?" Red Auerbach sweeps his hand to push the question away: "I don't want to go into that. That gets morbid." At the same time, he answers my question. He asks, "Have you seen that statue?"

Before I get to the door, the bullhorn voice starts up behind behind me:

"M.L.! Hey, M.L.!"

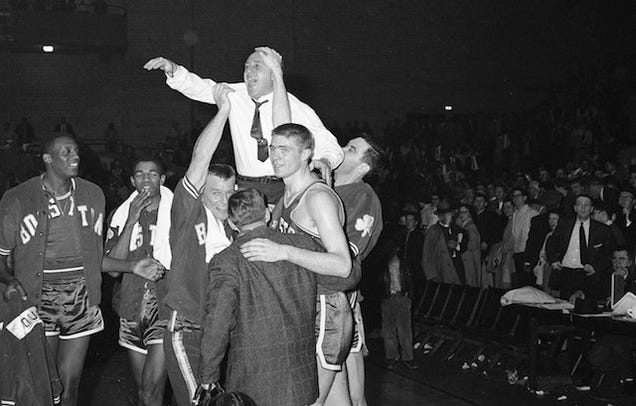

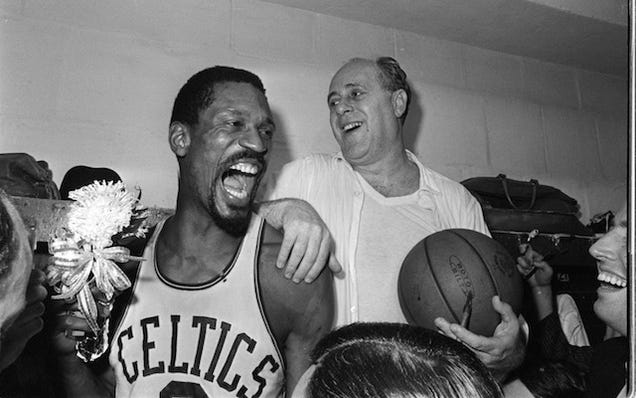

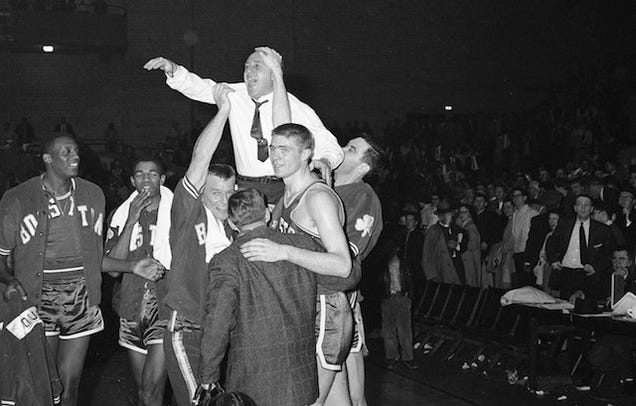

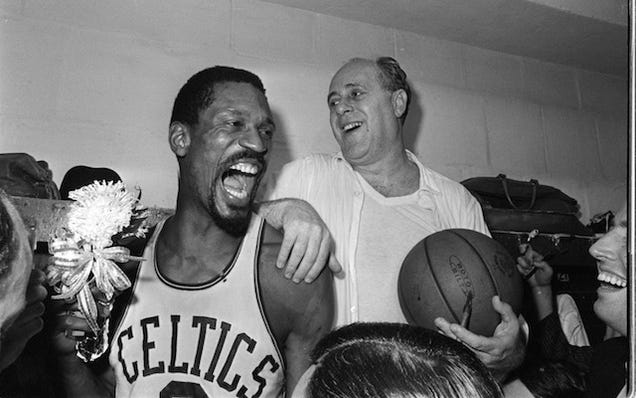

Photos via AP

bob

.

Donald Hall

Today 12:19pm

The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

The following was originally published in the Dec. 1986 issue of Sport magazine. It is reprinted here with the author's permission.

Last year the City of Boston erected a statue of Red Auerbach in the Faneuil Hall Marketplace near the effigy of James Michael Curley, another shrewd benefactor of Boston who once was reelected mayor while serving a term in jail. In his latest hurrah, the bronze patriarch of the Boston Celtics sits on a bench upright and alert; fans and tourists sit beside him and get their pictures taken. He carries a clenched program in his left hand where the ring finger wears the jewel of an NBA championship. In his right hand he clasps an enormous bronze cigar, fondled so much by admirers that it shines like St. Peter's toe.

The statue's original keeps a large and cluttered den on Causeway Street in the Celtics' offices, which are connected by a bridge of sighs to the great leaky ark of Boston Garden. As I enter the office, the the first thing that greets me is a life-sized cutout of Red Auerbach smiling and gesturing—a two-dimensional statue which I start to address. While I sit facing the man, his cardboard image hovers over my right ear; when one Red Auerbach answers the telephone, I swivel my head to find another Red Auerbach looking down at me.

Auerbach's office occupies the building's corner with windows on two sides, so that you can look down at the surviving elevated tracks of Causeway Street. The glorious junk of a lifetime overflows this room. Several hundred photographs on the wall mostly picture tall young men wearing shorts; the family pictures of the multitudinous sons. I count at least 20 caricatures of the father figure himself. On the desk, on a table and on shelves extending from a wall are dozens of letter-openers from Auerbach's extensive and global collection: blades that look like steel, ivory, pewter, bronze; handles of ivory, gold, cloisonne, enamel. The whole collection approaches 500, but much of it stays in Washington, where Auerbach has retained residence while commuting to Boston for 36 years. On the wall hangs a jacket from the Washington Caps, Auerbach's first stop as a professional coach, in 1946. There are framed citations, trophies galore, mementos that look like toys for grown-ups—a small cannon, a boomerang, basketball dolls—a painting that features Jo Jo White, plants, books and wood sculptures that look African and Oriental.

He hangs up. We talk. In July of 1986 Arnold (Red) Auerbach has come north to Boston for the first time since his latest sports injury. Playing tennis earlier in the month, this sexagenarian leapt for a ball like Larry Bird (whom he beat on the courts several years ago; "How can you let yourself be beaten by a 65-year-old man?" taunted Auerbach) and laid himself up. "I dove for the ball. Boris Becker! A poor man's Boris Becker! I just dove flat out for it, got the ball back and tried to roll over… bang! I hit the deck and broke two ribs." It is noted that he got the ball back; it is noted that he lets us know he got the ball back. This is the same ancient fellow who, three years ago in exhibition season, lost his temper and tried to assault Moses Malone. When I remind him he laughs. "Billy Cunningham called me up the next day. 'Goddamn!' he says. 'You never change!' " As he laughs the lines that ray from his eyes deepen, and for a moment he looks like a man in his 70th year. He sits slightly stooped, his once red hair a sparse grey. His physical self seems shrunken, or at least smaller than the whole presence of the man. But the energy that he exudes—even lounging back in his chair speaking mildly—removes the wrinkles one by one until his age is invisible.

Red Auerbach intends to work out three times a week—"racquetball, tennis, something to get a little sweat up"—but he no longer challenges his players at HORSE. "As you get older," he acknowledges with a sigh, "the ball gets heavier." His former all-star Bob Cousy, 11 years younger than Auerbach, meditates now on "banking the fires of competition," as he tells me; if you are unable to cool down the flames, says Cousy, the author of The Killer Instinct, they burn the lining of your stomach.

When I mention Cousy's endeavor, Auerbach nods his head. Leaning back in his chair, puffing at his logo, surrounded by trophies of the life lived, he speaks softly: "It's just age," he says. "You've got to learn to adjust to the limitations. It's difficult…" I realize that, unlike his old point guard, Auerbach struggles with match and kerosene, not with fire hose; Cousy is not president of the Boston Celtics. "You try to keep up the fire," says Auerbach, "but you find that you need, oh, a little more rest… a little more away time." He blows out a great, enveloping, blue cloud; it smells good. "If you don't have that driving interest, it's transmitted to the coaches and players; they feel it."

He has been speaking almost dreamily, in a soft voice rather high in the register, milder and more reflective than I had expected. In his autobiography he called himself an introvert, which startled me until I realized that everybody, even the wildest public man, knows in his secret heart that he is an introvert. When I questioned him about the word, he explained, "It's a guy that likes his own privacy."

Suddenly he blasts me out of my chair with a booming horn of a voice, as he looks past me to the corridor outside. His voice drops eight octaves and rises 400 decibels; his accent becomes street-Brooklyn, like Archie in the old "Duffy's Tavern": "Hey! M.L.! Don't go away!"

Leaning gracefully against a doorjamb is the tall and elegant form of M. L. Carr, who played in the Celtics' backcourt from 1979 to 1985. As I catch sight of him he pirouettes lightly, stylish as Baryshnikov—and dressed to the nines in polished shoes, crisply creased grey flannels, green blazer, white shirt and striped tie. He tilts his head back to regard Auerbach who bellows again: "M.L. Don't go away!"

M.L. adopts a studied look of puzzlement and speaks in a teasing, high-pitched, pondering voice: "Now that's interesting, you tell me that… a year ago, you told me to go away!"

Red Auerbach laughs. "Okay," he says. "Go away but don't stay away."

We all know whose shrewdness assembled this team. For 20 years Frenchified sportswriters, talking about the Boston Celtics, have gone to Larousse to spell the ineffable; they find mystique, easily the most overworked gallicism since Chevrolet coupe. Dissidents have been quick to repair the orthography: R-u-s-s-e-l-l in one era, and B-i-r-d in another. But the true orthography—in one era and out the other—is A-u-e-r-b-a-c-h, and there has never been another such institution in American sports. In 16 years as the coach he won nine championships; in 36 years of running the show, he has collected 16.

Houdini—or call him Diaghilev or Peter Sellars or Thomas Alva Edison—began life in Brooklyn in 1917, son of an immigrant from Minsk who worked his way up to owning a dry cleaning establishment. (Auerbach still presses his own trousers on occasion at a friend's shop; it takes him back.) His father Hymie's character, Auerbach says, differed from his own: "Everybody liked him." He admires his father and like many men who admire their fathers, he admires fatherhood. To his team he has been protective, fair, difficult, tender, demanding and above all, paternal.

The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

Although he admires his father's easy popularity, he made good use of his own abrasiveness. "At first I didn't like Red Auerbach," says a rival coach, "but in time I grew to hate him." If you spend energy hating Red Auerbach, maybe you do not play so well against him.

In street and schoolyard, young Auerbach became an athlete, as sport provided exit from Brooklyn to college by way of scholarship. His potential as a pro was not an issue in 1940, when he could pick up $20 maybe by driving to Wilkes-Barre to play semipro. He had majored in physical education in order to become a teacher and a coach. After college—team captain his senior year, high scorer—he picked up his M.A. at George Washington University while coaching at St. Alban's Prep in Washington. He worked for the city on playgrounds, refereed and then taught while coaching at a Washington high school. An early academic triumph was the publication of an article in the Journal of Health and Physical Education in March, 1943, on the construction and utility of indoor obstacle courses. (High school students trained for combat in 1943.) In 1986 in his office on Causeway Street, Red Auerbach reaches into a bookshelf and hands me the Journal, opened to his paper. "I had the centerfold, see? 'A.J. Auerbach, Roosevelt High School, Washington.' "1

Even when you are 69 and there is a statue of you in town you take pride in the byline that glorified your 26th year.

After three years in the wartime Navy, Auerbach began his professional career in 1946, coaching the Washington Caps of the newly founded Basketball Association of America. In 1950 he came to the Boston Celtics. He was hired by Walter Brown, who owned the team and was losing his shirt. In recent years a ticket has turned hard to come by; it was not always so. When the Celtics with Bill Russell won 11 championships in 13 years, they sold out only for playoffs. Basketball was for New York and Indiana; in the north country, hockey was the sport.

The New England exception was Holy Cross, and chauvinist sportswriters ignorant of basketball made a shrine of Holy Cross—1947 NCAA champs, a 27-4 record in 1949-50. That spring when Auerbach, at his first news conference as Celtics coach, was asked if he would draft the great Holy Cross senior Bob Cousy, he referred to the demi-God as a "local yokel." Enemies he made in that moment hectored him for decades. Later, in order to stop an idiot chorus claiming that Holy Cross could beat the Celtics, Auerbach scheduled a scrimmage; predictably, pros kicked college ass.

Auerbach's notions about roundball were set long ago. He praises his coach from George Washington University, Bill Reinhart, and he repeats the theme that the game has not changed. Bodies get taller and quicker but the game is the same. "I was always a fundamentalist. Like my book." He refers to Basketball for the Player, the Fan and the Coach. "It's in seven languages. It was written in 1952. Most of it is applicable to today's game."

There have been innovations and he has not always favored them. Twenty years ago he was vehemently against the suggestion that the NBA install a three-point shot. "I was wrong," he says quickly. Over 69 years you have the opportunity to be wrong about many things, and the president of the Boston Celtics is quick to proclaim his error.

Of course many modern wrinkles are Auerbach's own, tried out not in practice or even at rookie camp but on schoolyards in the Washington summer. When Auerbach relaxes from professional basketball there is nothing he likes so much as to watch basketball. "I go to watch high school. Even today, it's nothing for me to go watch a summer league. I go out to Maryland or Georgetown or George Washington, and I watch teams practice.

"Some of the best plays I ever devised were on the playgrounds. We'd get there early, guys like Elgin Baylor, Dave Bing, guys around Washington, even as professionals, working out on a Sunday morning in the playground during the summer. Sometimes I'd get there a little early, and I'd say: 'Look, I've got an idea.' If we could do it on the playground, we could do it in the NBA. That's where I invented all those out-of-bounds plays, when people line up across the court."

He stubs his cigar out in an abundant ashtray. From time to time he glances into the corridor. I ask: "Do they keep coming back, like M.L.?" He nods: he is happy. The sons return; they grow potbellies and grey hair, but they are sons and they return. "I talked to Ramsey just two days ago. I know where every one of them is. Gene Conley down the street, Finkel, Kuberski, Satch, Havlicek. When they're not around, I talk to them; I talk to Macauley; I even see Bones McKinney now and then." Bones McKinney was a 1946 acquisition for Auerbach's Washington Caps; he played for the Celtics late in his career. Although Bill Russell lives in Seattle, "I see him all the time because he works for TBS. I see his daughter. She's at Harvard Law School. I see her all the time."

In a moment he walks around the desk to the great humidor of cigars. He offers me one which I refuse; then I change my mind. I pick one out and cherish it into an inside jacket pocket.

Auerbach's affection for Bill Russell bobs up continually as he speaks, and when he talks about the particulars of basketball his examples are Bill Russell first. "Who is the best athlete you ever coached?" He will list Cousy, Sharman, Gene Conley (who played major league baseball and basketball at the same time) but first he will say, "Russell was a great athlete!" Even more than his athletic ability, it is Russell's integrity and brainpower that Auerbach returns to again and again. Integrity, and frequently the want of it, is an Auerbach theme. There is a tolerable difference for Auerbach between doing everything to win a game—everything legal—and going back on your word. He is old fashioned and upright about handshakes and agreements. "Integrity" and "brightness"—both attributes of Bill Russell—salt his speech. "He is very bright, Russell, very bright."

The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

There are other favorites, even outside basketball. His daughter Randy works for Mel Brooks; Brooks has become an Auerbach crony: "I went over there with Larry Bird one time, and he entertained us for an hour and a half!" He laughs and shakes his head; he cannot provide examples. Brooks is a good man, who cares for the people around him, he tells me. Then he adds, "He's not only funny, he's bright."

I talked with Bob Cousy a week before seeing his old mentor, and Cousy handed me a ticking package: He suggested that I ask Arnold (as Cousy likes to call him) if the Celtics had recently instituted a racial quota system. Predictably, Arnold glowers: "He's kidding," he says quickly.

There are many ways to hate the Boston Celtics. Recently a prestigious form of Celtic hatred has become disapproval of their pale lineup. Residents of Princeton, New Jersey—a city noticeably monochrome—shake heads noticing that gray-boys form two-thirds of the Celtics' team; Knicks fans who live behind doormen on Sutton Place deplore the Celtics for starting three whites out of five; in Los Angeles film producers driving DeLoreans regret the irrefutable fact that the Celtics can play six whites not including Larry Bird and Kevin McHale. Never has so much civil rights fervor been expended in the service of athletic partisanship by so many rich white folks.

Any ground for suspicion lies not in Celtics history but in the city where the Celtics practice their craft. Boston is infamous for racial intolerance and so are its Red Sox. But Auerbach's record is clear. Which team in the NBA was the first to draft a black player? Which was the first to start five black players? Which was the first to hire a black coach?

Auerbach refuses to take credit. If you take credit for playing blacks you must take blame for not playing them. "It's all crap! If a guy can do a job we don't care about his color. It just happens!"

I expected Red Auerbach to be shrewd, smart and competitive; he is all these things—and he is softer than I expected, less harsh and more of an aesthete, even as an observer of basketball. The fast break is his favorite play for winning, and winning is his favorite occupation—but for the beauty of it, his favorite play is the pick-and-roll; "It has to be timed just so; the guy with the ball has to make a decision whether to go, to shoot or to pass." As he speaks his hands gesture and he smiles with something like tenderness; he is like a gourmet describing the best omelette he ever ate, or a theater-lover the best Hedda Gabler. Red Auerbach loves precision of execution—in basketball, in tennis, in baseball and in letter-openers.

For 20 years and more, Auerbach spent part of each summer in Europe, Africa and Asia, generally accompanied by a large assistant, to give clinics and spread the word about the American game, NBA version. He loved these trips, sponsored by the United States Information Agency of the State Department. He took Don Nelson with him, Bill Russell of course, John Havlicek, Tom Heinsohn, Bob Cousy—to Japan, to Taiwan, to Burma, to Bangkok and all over Africa. Wherever he went, he held his clinics in the morning, so that in the afternoon he could shop. "I bought silver, ivory, cloisonne... I know a lot about that stuff." While teacher Auerbach was holding clinics in basketball for citizens of Bangkok in the morning, in the afternoon he was teaching silver, ivory and cloisonne to his tall dependents.

I ask him: "Is your Washington house full of this stuff?"

He shakes his head smiling; it is another happiness, like his continuing friendship with old players. "Unbelievable!" he says.

Red Auerbach's two daughters grew up in Washington among the unbelievable possessions, but largely in the absence of their father. I have never talked to a grossly successful man, late in his life, who did not regret the childhood of his children. Auerbach's team-family took precedence over the family of flesh. These days he sees more of his real family—and he wants them to have things now, not after he is dead—but continually he argues with himself about the years of separation. "If anybody ever tries to tell you that they are not affected at home by what happens on the court, they're lousy coaches. Bad as it was, being away from my family, it was a blessing in disguise. Most coaches with their wives are relatively unhappy."

He still flies to Boston for many home games and listens in Washington on a radio to the rest, hearing the redoubtable Johnny Most (greatest Homer since the blind poet). He also leaves home to lecture, maybe three or four times a month. Sometimes he talks for bread and butter, often he talks for charities; he lectures at Harvard five times a year, a class in sports law.

Every summer he comes to Boston for rookie camp, and at the same time he runs his own one-week basketball camp—with college players as counselors. Len Bias was a counselor at Auerbach's camp for three years, which was how Auerbach came to know and cherish him. The death of Len Bias is not for talking about. It is the only true darkness I feel in this man. When I mention Len Bias I feel like a ghoul. Auerbach swivels his chair aside; he looks away for the first time in the interview; his mouth does not want to open. For Red Auerbach, this is the worst thing that has happened in all the years of basketball.

As I prepare to leave, I ask Red Auerbach a final question which I keep to the end because I figure that I won't get anywhere with it. In a sense I don't, because it is the only question that makes him impatient. I ask: "Do you think about dying?" Red Auerbach sweeps his hand to push the question away: "I don't want to go into that. That gets morbid." At the same time, he answers my question. He asks, "Have you seen that statue?"

Before I get to the door, the bullhorn voice starts up behind behind me:

"M.L.! Hey, M.L.!"

Photos via AP

bob

.

bobheckler- Posts : 62620

Join date : 2009-10-28

Re: The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

Re: The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

On Johnny Most....." greatest Homer since the blind poet" OMG too funny !!

beat

beat

beat- Posts : 7032

Join date : 2009-10-13

Age : 71

Re: The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

Re: The One Question Red Auerbach Wouldn't Answer

A really thoughtful interview and story about Red. I sat in that office one day, when he gave me three thousand tickets to sell for Sam Jones day, with all the proceeds to go to Sam. He graciously chatted with me for a while, and I asked what he thought was the reason why the Celtics didn't draw better. "Simple. We win too much. We take all the mystery out of it. Some day, they'll appreciate the wins and flock to the games. But not until we've had a losing streak."

He didn't say it, but I'm sure he would never have gone on record as regretting the tradeoff of winning so much yet attracting so few. Red Auerbach was many things in basketball and in life; but, first and foremost, he was a winner!

Sam

He didn't say it, but I'm sure he would never have gone on record as regretting the tradeoff of winning so much yet attracting so few. Red Auerbach was many things in basketball and in life; but, first and foremost, he was a winner!

Sam

Similar topics

Similar topics» Rajon Rondo Is The Question Without An Answer, Again

» Markelle Fultz vs. Lonzo Ball: The NBA draft question Danny Ainge's Celtics may soon have to answer

» "The Answer" Retires

» The Answer vs Mighty Mouse

» Why Blake Griffin could be the answer for the Celtics

» Markelle Fultz vs. Lonzo Ball: The NBA draft question Danny Ainge's Celtics may soon have to answer

» "The Answer" Retires

» The Answer vs Mighty Mouse

» Why Blake Griffin could be the answer for the Celtics

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum